Picture this: a Budapest whose downtown is bordered by the gently flowing Danube from all sides, with a huge, New York-style high-rise scraping the sky at its centre, overlooking an imposing, 1000-metres tall pyramid sitting atop Gellért Hill. Sprinkle it with a grandiose synagogue balancing on the line between Art Nouveau and Art Deco, and a whole new avenue that would’ve run parallel to Andrássy út, and you’ve got the makings of 2019’s first Budapest Uncovered!

Skyscrapers

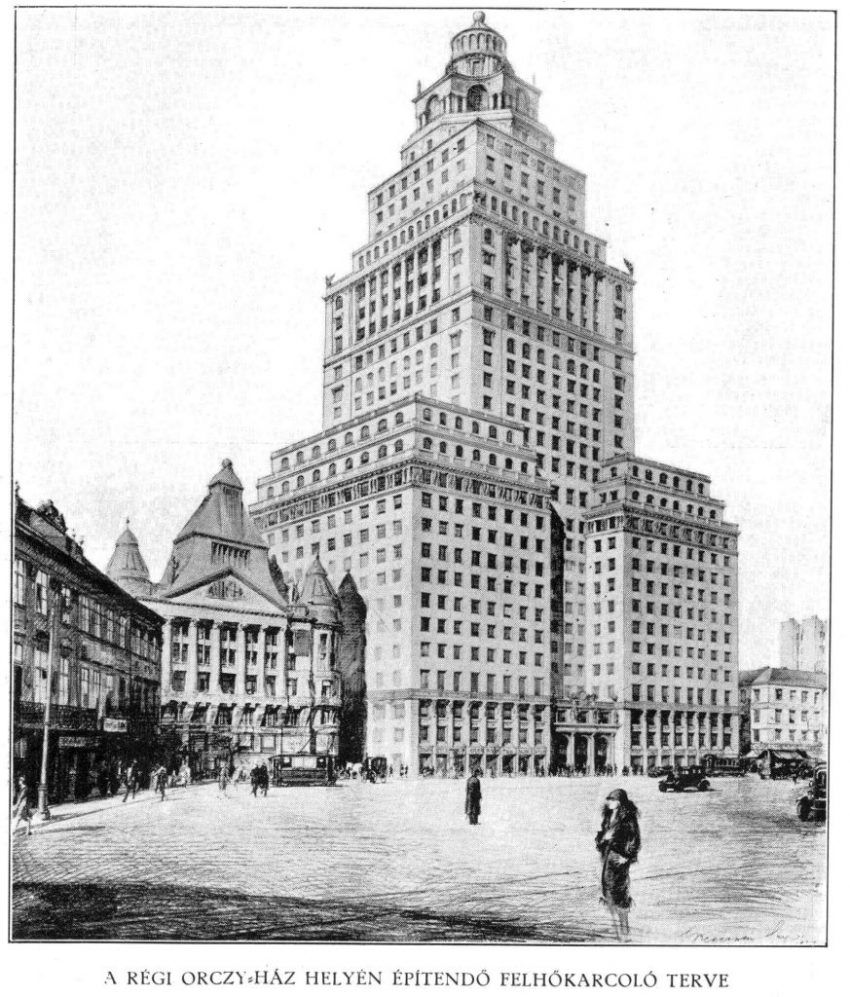

The economic boom of the 1930s brought something new to the table of Budapest’s architects: a chance to design and plan towering skyscrapers that would proclaim for the whole world to see the power and wealth of governor István Horthy’s Hungary. The most prolific skyscraper-architect of this epoch was undoubtedly Hugó Gregersen, a man of Norwegian descent, whose plans for the Orczy and Rókus skyscrapers (composed of 34 and 27 floors, respectively) were scrapped in favour of more cost-efficient alternatives, including the red-brick Madách buildings that would’ve functioned as the gate to the city’s second avenue, to be named after Queen Elizabeth. This boulevard (connecting the downtown to City Park) suffered the same fate as Gregersen’s skyscrapers, and was abandoned in 1939 because of the project’s costliness. Today’s Városháza Park would also look a lot different if any of the handful of works submitted for the Town Hall design contest had become realized. For instance: if it’s up to architects Kertész and Weichinger, today there would stand an elegant, American-style skyscraper where the park and the Deák tér Evangelical Church are located, complete with a 30-storey high clock tower.

The Great Canal

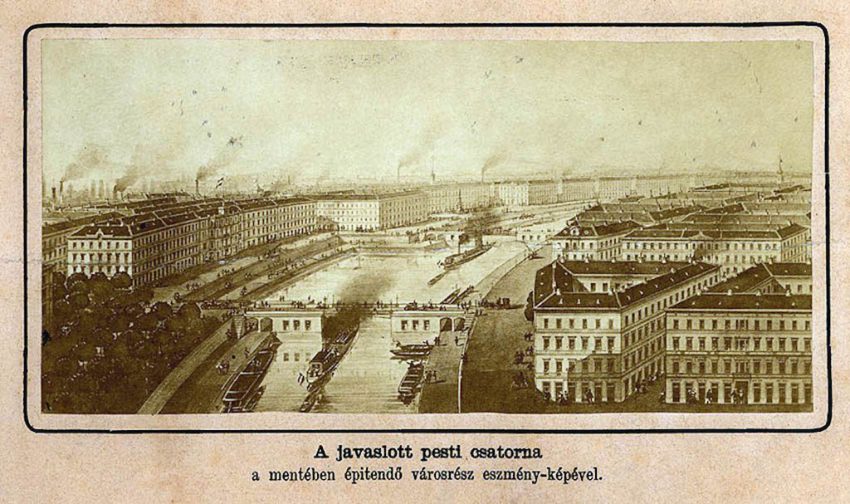

The idea of opening a canal in a former distributary channel of river Danube came to Ferenc Reitter, the first engineer of the Public Works Council in 1868. According to Reitter’s plans, the navigable waterway would’ve taken only four years to construct, and a sum of about 11 million forints (the Parliament building set the state budget back by 19 million). The canal would’ve been 2.5 metres deep and 36 metres wide, with 12 bridges crossing over it, 48 jetties, and sluices separating it from the Danube at its northern and southern ends. Unfortunately, the project was cancelled due to financial problems, and the canal’s planned route eventually became what is known today as the Grand Boulevard.

Lipótváros Synagogue

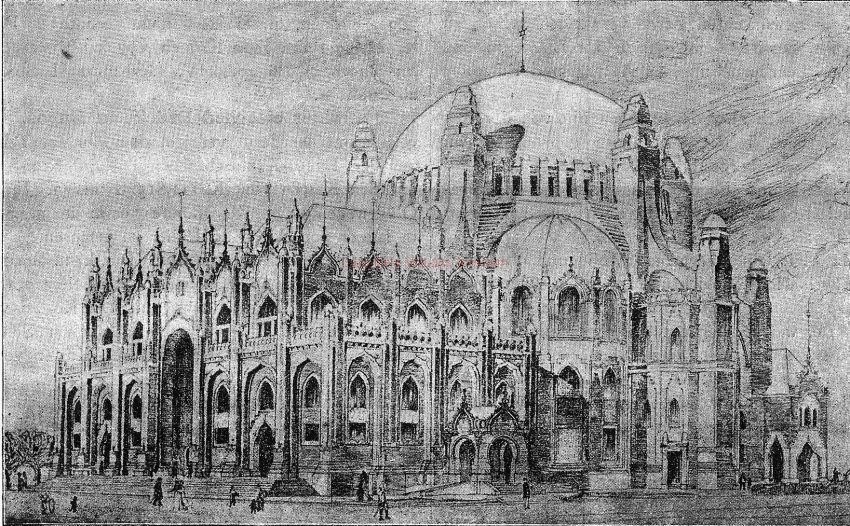

During the second half of the 19th century Budapest was the scene of a true Jewish renaissance, with such beautifully constructed places of worship springing up from the ground as the Dohány, Kazinczy, and Rumbach utca synagogues, each one pertaining to a peculiar style of architecture. And even though the city has nothing to be ashamed of when it comes to sizable synagogues, none of the aforementioned temples would compare to the grandness of the unbuilt Lipótváros synagogue. There were all in all 23 plans submitted for the 1899 design contest, which only had three stipulations: 1) the building must be free-standing, 2) it must have a seating capacity of at least 3,600 people, and 3) it must not cost more than 1 million forints. Although there were some real masterworks among the submitted proposals (including a plan by Béla Lajta, designed in late Art Nouveau style based on Byzantine architecture), sadly, none of the architect teams could drive the cost estimate below the amount specified by the local Jewish community: the double-dome (40+30 metres) of Ernő Foerk’s and Ferenc Schömer’s winning proposal would’ve cost 6 million forints alone.

National Valhalla

The last in the line of imposing but unrealized Budapest projects is the so-called National Valhalla monument, whose idea first popped up in the mind of the great reformer count István Széchenyi, then was taken up by his son Ödön in 1871: they envisioned the construction of a Pantheon-like structure on top of Gellért Hill that would’ve paid tribute to the heroes of Hungarian history. Apart from planting a couple of trees and tweaking the Citadel a bit, not much happened in the coming decades. However, at the turn of the millennium, a newfound interest in building a great memorial gripped the imagination of architects: the German Adolf Willheim conceived plans of a Ionic-style acropolis, complete with a giant statue of Lady Hungary, István Medgyaszay’s monumental Pantheon was to be topped by a dome shaped like St. Stephen’s Crown, while someone went as far as to make an impossible (and anonymous) suggestion of building a 1,000 metres-tall pyramid in the place of Gellért Hill, signifying the glory of the 1,000-year old Hungarian state. First, the outbreak of WWI, then WWII made sure that none of the grandiose plans were ever carried out.

Márton J. Vizy