This year marks the 170th anniversary of the Revolution of 1848, the longest revolution of the Spring of Nations. Although it was crushed by the Austrian and Russian armies in 1849, it had a major impact on freeing the serfs, and consequently led to the birth of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Here are some of the revolution’s most important Budapest venues!

Café Pilvax

Just as tea was the indirect cause of America’s war of independence, so did coffee have a crucial role in igniting the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Café Pilvax was a popular meeting place of radical intellectuals and the political youth of the budding city of Pest. It was here that on 15 March, poet Sándor Petőfi wrote and recited his famous poem, the National Song, as well as drafted the 12 Points, ultimately setting aflame the torch of revolution. The original building was torn down in 1911, in large part thanks to Pilvax losing its popularity among the intellectual circles to other, fancier cafés. Still, another café by the same name was soon opened, just a few meters away from where Petőfi and his friends made history, on the corner of Városháza utca and Pilvax köz.

Landerer Printing House

The Landerer family moved to the Kingdom of Hungary in the 1700s from Germany, and set up a number of printing houses all over the country. The Landerers have played a leading role in the country’s printing press scene for more than 150 years, their most notable contribution being the printing of Petőfi’s revolutionary poem, the National Song, the 12 Points (a list of demands made by the leaders of the revolution, including their requests for a national bank, the abolition of censorship, and civil and religious equality before the law), and the Kossuth banknotes. The building of the printing house (designed by architect Mihály Pollack) still stands to this day, under 3 Kossuth Lajos utca, right behind the beautiful Saint Peter of Alcantara Church, one of the gems of Ferenciek tere.

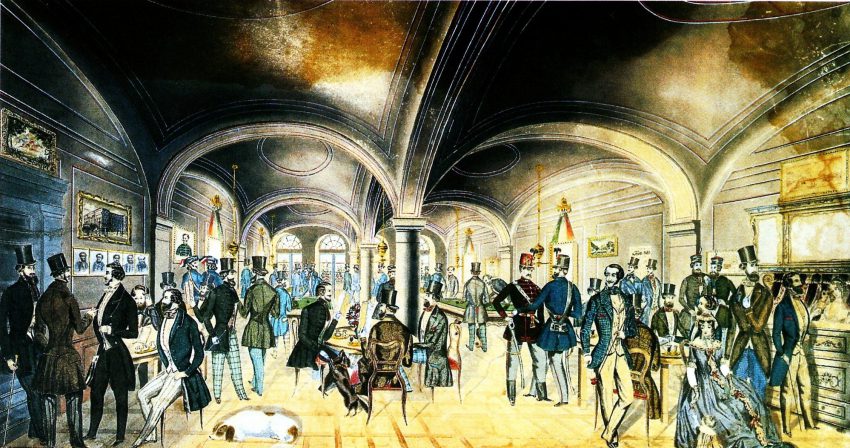

National Museum

At the time of the start of the revolution, the National Museum was the newest and shiniest building of Pest: Mihály Pollack’s classicist masterpiece was opened on 24 January, 1848. Just a couple of months later, it had become one of the iconic spots of the revolution.

It was in the front yard of the museum where the people of Pest (numbering around 10,000) first gathered together to listen to Petőfi’s National Song, recited on the front steps of the building. Spurred by the poem, the aroused crowd started its rebellious march for equality, liberty and brotherhood. By giving place to some of the country’s most treasured collections, and at the same time serving as a symbol of national freedom, the National Museum is Hungary’s most emblematic location.

Táncsics Prison

After paying a visit to the nearby Buda Chancellery (where all of the demands formulated in the 12 Points were agreed to by the council), the revolutionary crowd left to free the teacher-journalist Mihály Táncsics, one of the first Socialist politicians of Hungary. As his prison (found under 9 Táncsics Mihály utca in the Buda Castle, built in top of the ruins of the Medieval Kammerhoff, the Royal Mint) had no bars on the window, just some wooden boards, the crowd had a fairly easy time. When the boards were removed, Táncsics simply stepped through the window and into his escape carriage. The building was owned by the U.S. government from 1948 to 2014, when it was returned to the Hungarian state upon an agreement made by George W. Bush in 2007.

Szabadság tér

Little do Budapesters know that where present-day Szabadság tér stretches, bordered by beautiful and grand turn-of-the-century buildings, once stood the giant reminder of post-revolution Habsburg tyranny: the Neugebäude (New Building). It was inside this building’s giant courtyard (from time to time giving home to chariot races) where count Lajos Batthyány, Hungary’s first prime minister was executed. His place of execution is now marked by a sanctuary lamp. The building was commissioned by Emperor Joseph II in the 1780s, and was first used as a barrack, then as a prison, until it was finally torn down in 1897, giving place to architect Antal Palóczi’s magnificent Szabadság tér.